Bryon Lewis’ career began in the era of segregation when African Americans were ignored by the advertising industry. With his agency, UniWorld Group, now over 50 years old, the ad veteran looks back over an amazing legacy that changed the world of advertising.

In 2019, multicultural advertising agency UniWorld Group (UWG) celebrated its 50th anniversary. Two decades into the 21st century, the organization stands as a small but influential part of the landscape, an enduring story of success. But when Byron Lewis founded what would become the longest-standing agency of its kind back in 1969, it was a herculean project, an uphill struggle to demonstrate its value to a hostile and indifferent industry. Lewis not only succeeded against the odds but helped to build an adland with many more opportunities for minorities.

Mr. Lewis’ insight

Lewis was born on 25 December 1931 in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in Queens, New York. He graduated from Long Island University in 1953 with a BA in journalism, only to find the opportunities in the media for African Americans were extremely limited. “The United States was segregated, and I was not able to find any work in an area that I thought I could succeed in,” he tells us.

He served in the army and was employed as a social worker and other “short-term jobs” over a 10-year period, until, living in Harlem – then the “black cultural capital” of the US – in the ‘60s, he finally took the first steps on the long path towards UniWorld. He spent six months at the black-oriented newspaper Citizen Call before it folded, and three months at a magazine called The Urbanite, which quickly went the same way. The two publications’ shared fate stemmed from the same problem: “We could not generate any advertising revenue.”

“From that experience, I acquired a certain kind of understanding about the world that I lived in,” he continues. “If I was going to survive in any fashion, I had to learn how advertising worked and how I could fit into the industry. There were very few, if any, African Americans who had that background.” Lewis spent the next “seven or eight years” working across other black-oriented publications in Harlem.

As he honed his craft, he came to understand the two problems facing the African American community – that advertisers were failing to see its potential value and, even if they could, there was a lack of media in which they could speak directly to the community. With his awareness of these issues, Lewis was ideally situated to confront them. All he was lacking was the opportunity to demonstrate his skills.

That opportunity came in the form of a “chance encounter” in the late 1960s. “That was a period of affirmative action,” he says. “It was in the decade in which the Kennedy brothers were assassinated. Dr. King was assassinated. The industry – and I think the general nation – felt obligated to try to do something to change that pattern in the country.” Affirmative action was a policy of actively attempting to improve the fortunes and opportunities for minorities. In this climate, a white hedge fund called Fairfield Partners, feeling “that there was an obligation to try to help”, got in touch with Lewis. “They found me uptown and they decided to invest in a company, an advertising agency which I called UniWorld Group. They invested £250,000 in 1969.”

Turning points

But the founding of UniWorld is far from the end of the story. Fairfield had a good knowledge of the advertising industry and its board felt that they would be able to help Lewis’ new agency succeed. However, the general disinterest and lack of understanding of the African American market proved harder to overcome than anyone involved had anticipated. “For the next seven, eight years, we were not able to generate enough advertising to sustain the venture,” Lewis said in an interview with BeetTV. His investors came close to pulling out and putting UniWorld out of business – Lewis needed a breakthrough, and quickly. He was left to think things through over the Christmas holiday weekend.

He was “depressed as hell”, but in the middle of a dream he had “what the white people call an ‘epiphany’” – UniWorld should make a radio soap-opera-like those Lewis had heard in his youth. He envisioned the story of a black family much like his own – one that had moved north from their southern home – and the challenges they would face. With the assistance of an African American brand manager at Quaker Oats who understood the appeal of the project, UniWorld secured sponsorship for Sounds of the City, a show that ran for 39 weeks in 1974 and featured famous actors including Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, and Billy Dee Williams. The soap was a success, and not only saved UniWorld but served as a platform from which Lewis could – and would – win future business.

“I had to learn how to influence the mad men, who were all white,” says Lewis.

“There had to be a way to convince the client that they should support a marketplace they knew little about and also didn’t feel was the market for their product. I had a learning curve over almost 10 years of being unsuccessful. But that learning curve is really how I was able to survive at UniWorld.” UniWorld’s 50th-anniversary celebrations were a testament to his ability to learn, adapt, and convince his clients of the value of minority markets. Where Quaker went, other brands followed. In those early years, UniWorld won business from big names including Kodak, Craft, and Smirnoff. Lincoln Motor Company became a long-time client as part of the agency’s expansion into the Hispanic market; Colgate’s ongoing relationship with UniWorld has lasted two decades; in the early ‘90s, it ran a highly successful campaign for Burger King.

“Mr. Lewis is super smart and very thoughtful,” says Monique Nelson, the current CEO of UWG. “Many perceive him as shooting from the hip, but he is always building from his experience to find the best solution. I admire him for not being afraid to make a mistake or create something new.”

Talkin’ about Shaft

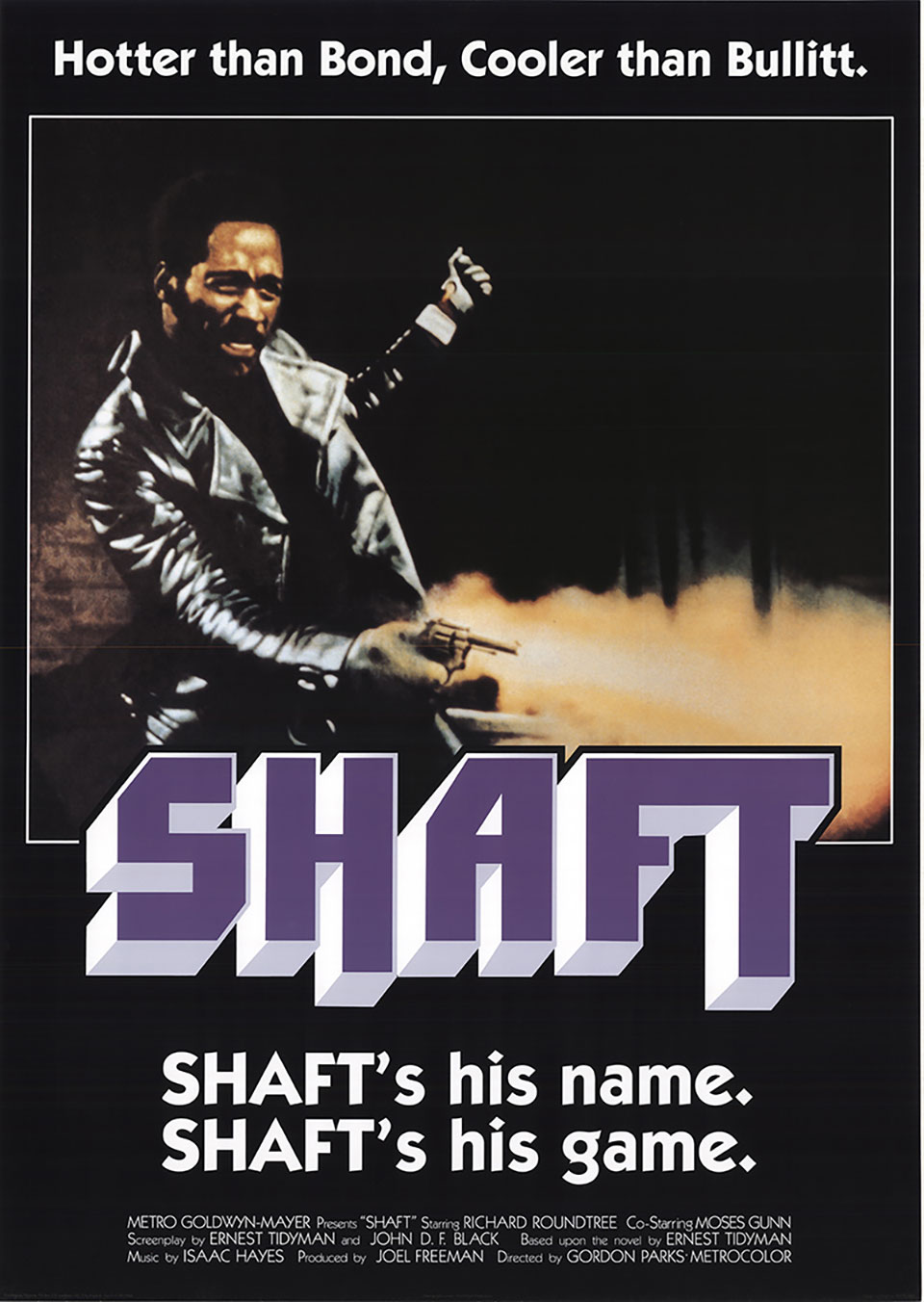

Perhaps UniWorld’s most iconic collaboration was on the legendary 1971 movie Shaft. The groundbreaking film, which was a huge crossover success with both black and white

audiences and helped to save the struggling studio MGM from bankruptcy, starred Richard Roundtree as the eponymous New York City private detective. The movie’s director was the multi-talented Gordon Parks, a musician, photographer, and writer. Parks was the first African-American to work as a staff photographer for Life magazine and also happened to be a UniWorld collaborator.

UniWorld was brought in to promote the movie, which resulted in Lewis and his cohorts creating a pioneering campaign that is considered the precursor to modern integrated marketing. Lewis collaborated with Stax Records – which had stars including Otis Redding and Booker T. & the M.G.’s on its books – and the label’s co-owner, Al Bell, who wanted to grow his brand. The result was Isaac Hayes’ legendary hit single, ‘Theme from Shaft’, which helped raise awareness of the movie through the medium of radio. “We felt that we could get the news about Shaft on the black-oriented radio stations, which were springing up at that time, and then we felt that [news of the film would spread by] word of mouth.” What they hadn’t anticipated was that the track would also be picked up by white radio stations. Both the theme and the film itself became huge crossover hits. “That had never happened before.”

“We learned about the power of black culture, black celebrity, black experience,” says Lewis, “but also – and this is something that I firmly believe – that black culture, through its music, is the basic communication power. Beginning of course, with gospel and blues, and today, hip hop. [The experience with Shaft] really convinced me that I had a chance to compete, I could reach a broader market, extend a positive view of black life and experience. That was the key to a 50-year career.” Lewis saw the untapped potential in the African American and other minority markets, but his motivation was always more than simply pragmatic. He wanted to make a difference. “It was my objective to provide a positive view of black life and experience in this country. I believe that UniWorld’s existence, and the things that I had to do to survive, provided a much broader understanding within the advertising industry of the importance of the individual black consumer and the power of a marketplace that was basically untapped. It also helped to bring a number of African Americans into the industry, not just within UniWorld, but the vendors, the photographers, the musicians, and the writers who serviced UniWorld and its clients through that period of time. We were able to provide exposure for a number of talented people in the arts, who were the subjects for our television commercials: actors, models, that type of thing.

“I’m proud of the contribution that we were able to make to improve the attitude of the advertising industry in general, at least in New York City. And we provided job opportunities for, over the years, thousands of employees and vendors.”

A lasting impact

Mr. Lewis’ legacy extends beyond winning high-profile campaigns with major brands. As part of his mission to increase the visibility of the African American community and its story by broadening the availability of media that targets the community (and which was so sorely lacking early in his career), he has been involved in some amazing projects. These include America’s Black Forum, a weekly news show that launched in 1977 and is one of the longest-running US-syndicated series on television; the PBS film This Far By Faith; and the American Black Film Festival, which he founded alongside Jeff Friday and director Warrington Hudlin in 1997 as the Acapulco Black Film Festival.

After 43 years at the agency he created and fought for, Lewis stepped down as CEO in 2012. “What I gained over the 50 years of being in business is an understanding of the importance of the African American female in the culture for African Americans, of the economic side and the spiritual side of our experience,” he says. “A large number of my staff over the 50 years were female, and in 2007 I hired a young woman named Monique Nelson.” Nelson had worked as a global marketer at Motorola, and after several years at UniWorld, approached Lewis with a proposition. “She said she would like to buy my stake in the company. I was interested, when I got into my 80s, in finding someone who could really take UniWorld to another world. The world, in my mind, had begun to change and I felt it was very, very important to find someone who could really take the company forward within an entirely different social and economic situation. The industry had changed. I felt UniWorld needed to change, and so I sold to Monique Nelson.”

“In an era when most, if not all advertising agencies were named after the proprietor, Mr. Lewis named the agency he founded UniWorld Group,” says Nelson. “He knew he was creating something that was meant to last. I am honored to build upon his legacy to blaze new trails. Mr. Lewis created a space where people of all backgrounds could collaborate and produce insightful and powerful work. It is a familial environment, where for the first time in my career I felt I did not need to wear my skin or gender to work.” In a hostile environment, Lewis not only survived but thrived – and changed the face of the advertising industry while he was at it. Through incredible tenacity and a willingness to innovate, he demonstrated not only the value of African American consumers but recognized his community’s ability to influence markets of any race. “Advertising is about storytelling,” he said in an interview on African American Legends, “and the stories I want to tell are about what I call pride and providence.” His own story of pride and providence may be one of advertising’s greatest.

It is my pleasure to have been a part of the UniWorld legacy. I am so proud of the agency’s contribution to black culture and the opportunities provided to tell our story in a powerful way. Thank you Mr. Lewis for your vision and insight. The lessons learned and knowledge acquired is still my mantra to approaching life. May God’s anointing on your life continue to keep and bless you.

Proud to have worked with and for Mr. Lewis. Creative, Strategic. Bullish. Generous. A titan. Good singer too. Only one Byron Lewis, Sr.