Today, New York is a bustling centre of culture and tourism. It’s a city with millions of people packed onto an island where skyscrapers block out the sun, but it’s also a melting pot for culture and a hub of creativity – a place where The American Dream is still alive and kicking. Perhaps it’s this vibrancy of urban life which fostered the wealth of talent and influence at the heart of its historically remarkable advertising industry.

In 1977, New York City successfully advertised itself.

In the early ’70s, the Big Apple was getting a lot of bad press. Desperate to save the city’s reputation, the Department of Commerce enlisted the help of its best advertising talent. In 1976, Jane Maas, later dubbed the “real Peggy Olson”, dreamt up the iconic I ♥ NY campaign for an advertising agency, Wells Rich Greene. It was a simple message and a logo crayoned on the back of an envelope by designer, Milton Glaser, but it captured the attention of the people and turned the image of a scruffy, dangerous city on its head. Since then, the I ♥ NY message has united the city in difficult times and the logo still features on almost every street corner, stamped on tourist t-shirts and keychains. In fact, almost every major global tourist spot has borrowed the I ♥ [insert destination] idea for its merchandise.

Over the years, New York’s ad industry has helped shape the city in more ways than one. In celebration of its many advertising successes, we’re taking a nostalgic look at its defining historical moments.

Broadway & 42nd Street, 1898

The early days of New York advertising

The New York advertising industry really kicked off around the turn of the 20th century, as the development of the finance and banking industries were turning the city into a global economic player. Some of the iconic agencies were just starting out—the company that became BBDO was founded in 1891 by George Batten, and McCann Erickson began with the opening of Alfred Erickson’s agency in 1902.

Over the next few decades, New York saw several defining advertising moments. On August 28, 1922, the first-ever radio commercial aired on New York’s WEAF, advertising apartments for the Queensboro Corporation. Nearly 20 years later, in 1941, the first legal television ad aired on New York Local Television, in the middle of a Brooklyn Dodgers vs Philadelphia Phillies game. It was a 10-second black and white advert for Bulova watches with the simple tagline, “America runs on Bulova time”. Compared to the colossal $5.25 million on average charged for a 30-second Super Bowl slot today, it cost the company just $9. These early moments helped cement New York’s position as an advertising giant.

Camel 1948: The Cigarette ad that literally let off steam through the smoker’s mouth

Madison Avenue and ‘the Golden Age’

No history of advertising could ignore the cultural and economic impact of Madison Avenue. That it’s now synonymous with the American advertising industry is a true testament to the power of the New York ad game, even if many of the major players have never worked off the famous street.

‘The Golden Age’ of the ’60s and ’70s is perhaps the most famous (and for some moments, infamous) period of Madison Avenue history. An era defined by big personalities and big ideas, it saw the creation of some of the most iconic campaigns of all time, including DDB’s rule-breaking ‘think small’ ad for Volkswagen and McCann-Erickson’s memorable ‘I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke.’ Agencies continued to pioneer industry firsts, from Young & Rubicam producing the first color television commercials to Mary Wells Lawrence becoming the first woman to found and run a major agency. On the flip side, it was also a notorious era of excess – making it a great story for AMC’s hit show, Mad Men.

A lot of this era has been accurately depicted in popular culture – three-martini lunches really happened and there were plenty of Don Draper-Esque characters creating poignant pitches like that famous Kodak Carousel scene in Mad Men. However, Keith Reinhard, chairman emeritus of DDB and co-founder of Omnicom, notes that other equally brilliant moments haven’t had their spotlight.

He draws attention to the creative revolution happening in the less polished agencies of ’60s Madison Avenue. Here, influential creatives, such as Bill Bernbach (the ‘B’ in DDB), were championing diverse teams of multi-ethnic employees living all over the city, not just the affluent areas. “The characters in Bernbach’s agency and the other revolutionaries he spawned brought a disruptive kind of madness to Madison Avenue that was nowhere apparent inside the comparatively starched and staid offices of [Mad Men’s] Sterling Cooper,” Reinhard explains.

With Bernbach and others rejecting traditional tactics, advertising got exciting. Campaigns stopped pushing hard sale points and told emotional, engaging stories to capture an audience—they made people laugh, they made people cry, and they made people pay attention.

The ’80s mega-mergers

Reinhard cites the “mega-mergers of the ‘80s” as one of the biggest historical changes in the industry, a shift that largely created the agency landscape of today.

These mergers were a response to crucial market changes. The world economy was improving and advertising spend was on the rise. Clients had money to spend and agencies wanted to invest in new acquisitions.

Clients now wanted international influence and a full range of services. So agencies needed to get bigger in every sense – they needed size to seem like global players, enough clients on the books to impress new business, to diversify their skills and offer more services, and enough people to make everything happen. The most notable New York merger was ‘The Big Bang,’ which saw three of the largest US agencies, BBDO, DDB and Needham Harper, join to create Omnicom Group.

The task of merging agencies was no small feat. To avoid client confusion (and any objections), mergers often happened in a frenzy after the market closed on a Friday and before it opened again on Monday. The personalities spearheading agencies sometimes made for a less-than-smooth transition. One famous bust-up was between David Ogilvy and Sir Martin Sorrell, the former calling Sorrell an “odious little jerk” for going after his company in 1989. But the merger train chugged on, and by the end of the decade, only four of 1980’s top 15 US agencies remained independent.

Commenting on the inevitable impact of mergers on company culture, Reinhard notes, “there is no question that, in the process, the industry lost colorful brands often led by colorful figures,” but this isn’t to say that the big players lack culture. He explains, “culture can be summed up as ‘what we believe and how we behave’ and those two differentiators are just as important—maybe more so—in a global network as in a boutique.”

The modern age and beyond

A lot has changed since ’80s Madison Avenue – globalization and the internet have certainly taken some focus off New York. But, as we go forward, we should remember what made the Big Apple’s great advertising moments great in the first place. As Reinhard notes, “what excites me most about the future is that we now have scientific evidence to prove what we have always known intuitively—the fact that emotion, not reason, drives human behavior.” This intuition is in the legacy of industry pioneers such as Bill Bernbach and David Ogilvy, the iconic ’60s campaigns that propelled brands like Coca-Cola to global recognition, and the powerful I ♥ NY campaign that turned New York into the bustling tourist hub it is today.

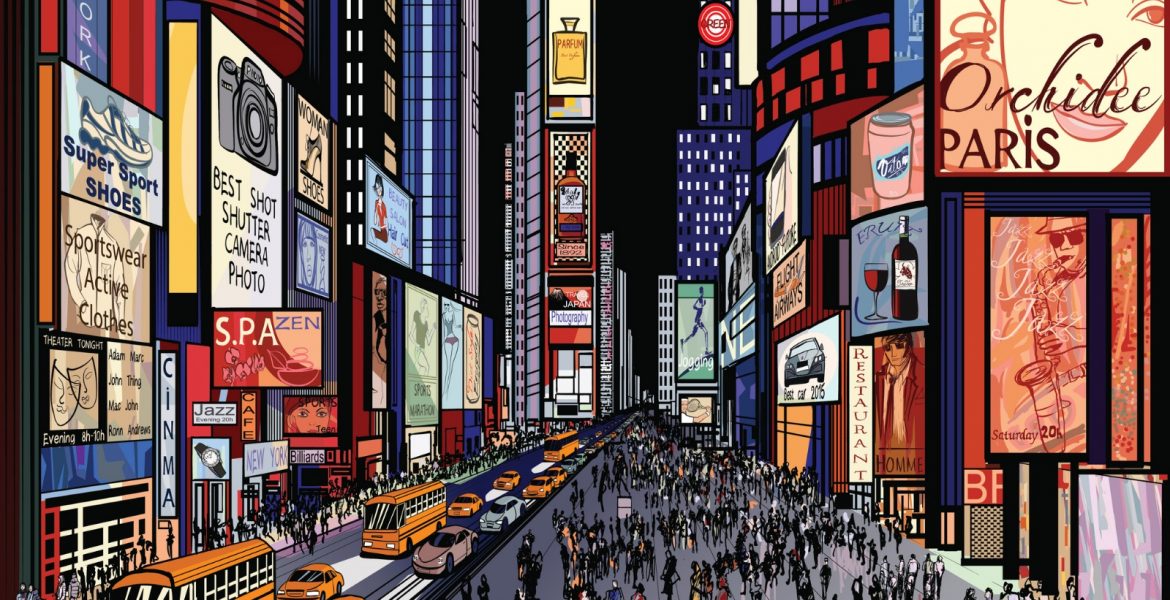

“Advertising is at its best when it engages and entertains to the point that people want to stop what they’re doing and watch it. Many of the mammoth electronic and digital displays in Times Square do just that.” – Keith Reinhard

Now here is the evolution and impact of advertising in New York City more visible than ‘The Crossroads of the World,’ Times Square. From the first electronic ad in 1904 to the Smart ads and LED screens of today, it has seen some of the most memorable, larger-than-life adverts of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Now here is the evolution and impact of advertising in New York City more visible than ‘The Crossroads of the World,’ Times Square. From the first electronic ad in 1904 to the Smart ads and LED screens of today, it has seen some of the most memorable, larger-than-life adverts of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Times Square is about size and impact, and new billboards continue to push boundaries. In 2017, Amazon constructed a 79-foot Echo, the square’s largest-ever installation. Later the same year, Coca-Cola broke records with the world’s first and largest 3D robotic billboard, setting a new benchmark for scale and technology. Reinhard believes this obsession with scale is unique in the ad industry, as so much advertising is now viewed on small screens. He wonders, “it seems to me that a moving image a full city block long could have more impact than the same image delivered on my iPhone. Does size matter? I think it might.”

But it’s about the experience and reach too, and many ads now have interactive and social elements. Reinhard notes, “not only are passersby entertained, but they can also be a part of the action and participate just as they do on social media.” And with approximately 330,000 people from all over the world passing through each day, that’s a tremendous global reach.

Chuck Hayden was the best Art Director the Avenue ever say -c. 1959 – 1985

Chuck Hayden was the best art director the Avenue saw, c. 1959 to 1985