The Trump campaign’s lawsuit against an NBC affiliate in Wisconsin raises an interesting question in rough-and-tumble politics: can a political ad defame?

Insults are fundamental to the genre. It is possible for politicians and political causes to defame each other. But it’s darn hard.

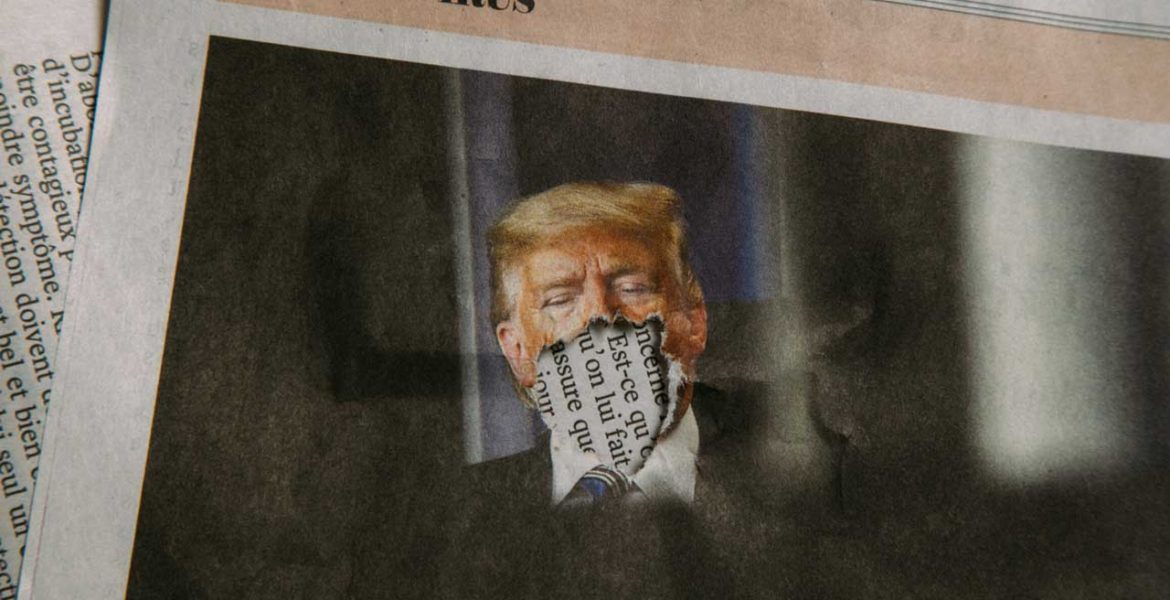

On April 13, Trump for President sued WJFW based in Rhinelander, WI, for unspecified damages because the TV station aired an ad critical of President Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis. The complaint said video spicing, a common technique, amounted to reckless disregard for the truth.

The Trump campaign’s lawsuit is part of Trump’s broader press-bashing. In quick succession, the Trump campaign sued The Washington Post, The New York Times, and CNN earlier this year for opinion commentary.

As a candidate and as president, Donald Trump said he wants to “open up” libel law to make it easier to sue media and collect damages.

Courts Grant Latitude for Debate

Regarding political discourse, the courts have granted wide latitude for sparring and criticism.

The Rosen-Tarkanian case from Nevada is a recent reminder that sharply worded, negative commentary in political ads is not necessarily defamation.

Nevada’s Supreme Court, in a 5-2 ruling on December 12, 2019, said candidate Danny Tarkanian’s defamation claim against opponent Jacky Rosen should be dismissed.

In their 2016 congressional race, Rosen’s attack ad linked Tarkanian to dubious charities. Tarkanian sued Rosen for defamation (Rosen won the 2016 House race; she was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2018).

In a legal victory for Rosen, Nevada’s highest court said:

- Those who engage in “good faith” communication on issues of public concern are immunized from liability under Nevada’s anti-SLAPP law (strategic lawsuits against public participation). A majority of states have such laws.

- In determining “good faith” communication, the court considered the whole meaning (the gist), rather than parsing individual words.

- Rosen’s claims “were substantially true.”

- Evidence did not show that Rosen’s ad was based on “actual malice.”

The actual malice standard was established in a landmark free speech/civil rights case in 1964. The U.S. Supreme Court, in New York Times v. Sullivan, said the robust debate is preferable to libel abuse that could chill free speech or silence criticism. To prevail in libel claims, the Supreme Court said in Sullivan, plaintiffs must prove that defendants had reckless disregard for the truth (actual malice).

In Iowa, candidate Rick Bertrand filed a defamation suit after his opponent’s ads criticized Bertrand’s role as a salesperson and manager for a pharmaceutical company. Bertrand, a Republican, won a state Senate race in 2010 by 222 votes.

A jury returned a verdict of $31,000 against Bertrand’s Democratic opponent Rick Mullin and $200,000 against the Iowa Democratic Party. But Iowa’s Supreme Court, in 2014, reversed the lower court and dismissed the case. Like the Rosen-Tarkanian case, the Iowa Supreme Court ruling illustrates the wide running room afforded to political advertising and commentary.

“Protection from defamatory statements does exist and should exist,” the Iowa Supreme Court said, “but the high standards established under the First Amendment to permit a free exchange of ideas within the same discourse must also be protected. Among public figures and officials, an added layer of toughness is expected . . .”

Quoting precedent, the Iowa court said free speech protections extend to debate about candidates’ character and fitness for office.

Conclusion

Presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard (D-HA) sued Hillary Clinton for $50 million (Tulsi Gabbard and Tulsi Now Inc v. Hillary Rodham Clinton). Clinton’s transgression, the suit claims, was her suggestion on a political podcast that a current Democratic candidate for president was a “Russian asset,” presumably Gabbard.

Gabbard’s legal complaint, filed January 22 in federal court in the Southern District of New York, called Clinton a “cutthroat politician” motivated by spite because Gabbard endorsed Clinton’s rival Bernie Sanders for president in 2016.

When one politician suggests that another politician is a Russian agent and that politician calls the first politician a cutthroat, it seems difficult to find a clear line between standard mudslinging and defamation.

Good luck, President Trump.