by Amit Sharan, VP of Marketing at Tatari

The latest revolt against Facebook is well underway. And while the participating brands cite ethical concerns as their primary motivation, many in the industry suspect that they have also tired of Facebook for other, more concrete reasons.

The same point is frequently invoked today: social media platforms have become saturated, and brands are thus forced to seek out new channels for growth. But what does saturation mean?

Saturation has been used to describe the percentage of companies that advertise on social, the time users spend on social media, or the slowing growth rate of revenue of the platforms themselves. None of these gets to the heart of the matter.

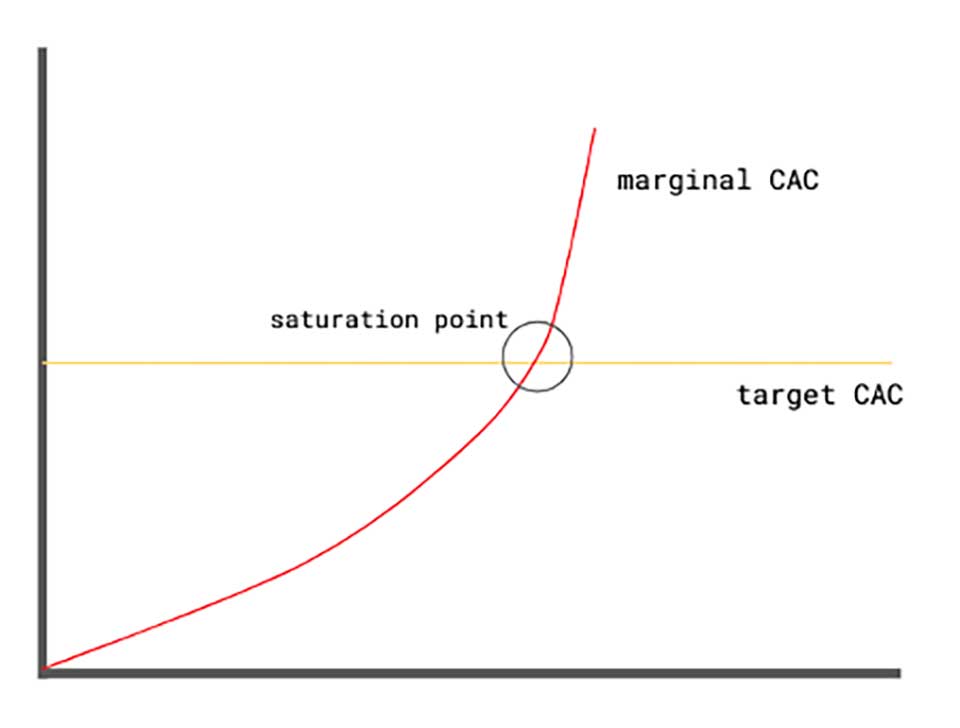

The saturation point in social media is where the marginal cost of acquiring new customers exceeds the target customer acquisition cost (CAC) for a given campaign. It is a specific mathematical point of diminishing returns, and despite the massive audiences on social platforms, even emerging brands hit it faster than they realize. New customer acquisition is always expensive (relative to retention), but there is a point at which it becomes too expensive.

Facebook is aware of the issue, as I can attest from personal experience. I spent over 4 years at Facebook and we knew that inventory was limited on the newsfeed. It’s why I joined a then newly-formed team focused on creating new surfaces that we could later monetize with in-stream video ads such as Facebook Live, Watch, and most recently IGTV. It’s also why they bought LiveRail (now folded into the Audience Network), so they could serve ads on other publisher’s websites and apps.

Facebook gets it – but do marketers?

Marginal vs. Average CAC

What most marketers miss is that the customer acquisition cost is simply an average cost. While it shows how much on average the marketer spent on each customer, it does not answer a vastly more important question — what was the additional cost of acquiring one more customer? In other words, what was the marginal cost?

It is essential to understand this distinction because optimizing advertising campaigns should always be done at the margin, and not at the average. As more customers are acquired during the campaign, the cost of acquiring an additional customer is likely to keep increasing. For instance, it will be more difficult and expensive to acquire the millionth customer than it was to acquire the first one.

The failure to properly differentiate between marginal CAC and average CAC is what leads many marketers to spend on platforms well past their saturation point. Marketers should understand the difference between marginal and average CAC and use the marginal cost to determine if they should spend more or less on each channel.

No platform is infinitely scalable

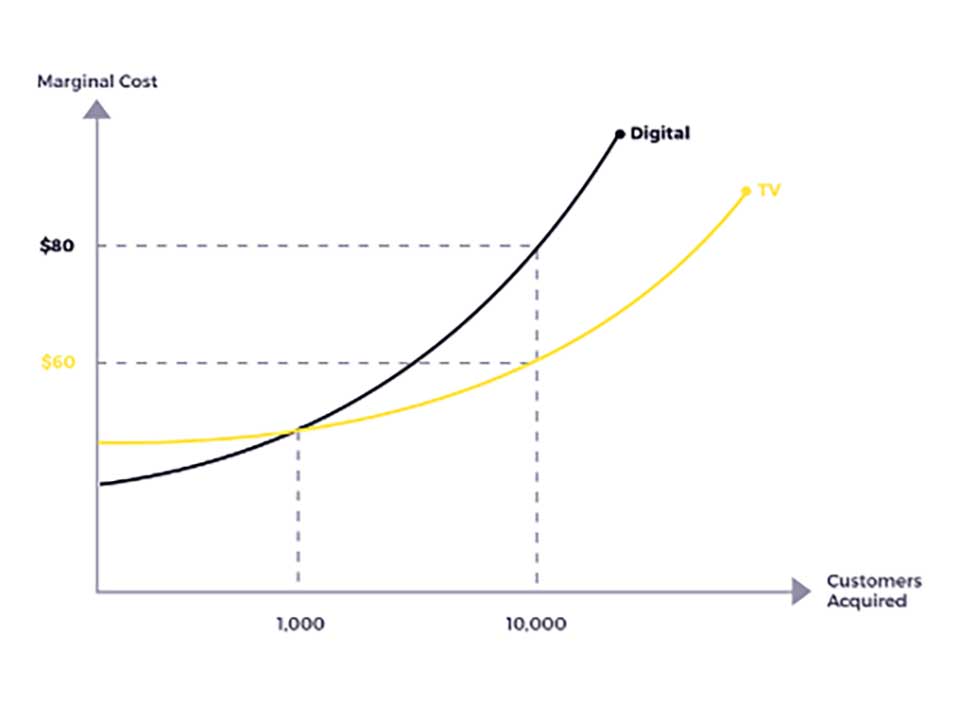

The ability to increase marketing spend (or acquire more customers) without quickly escalating marginal customer acquisition costs is often referred to as scale in the industry. Savvy marketers will seek channels that not only perform well (i.e. the marginal acquisition costs are low relative to other platforms) but also offer scale (i.e. the marginal acquisition costs do not escalate quickly).

Marketers can saturate even the largest platforms relatively quickly. Take, for example, a brand that wants to sell hiking boots to outdoor enthusiasts. The brand uses first and third-party data to create a lookalike segment of 5 million potential customers on Facebook. The brand runs successful campaigns, acquiring 5,000 new customers at an attractive CAC. The brand keeps trying ad campaigns and promotions, but the available pool of real prospects doesn’t grow significantly beyond what it was. Facebook continues to report an average CAC that is attractive to marketers, while the marginal CAC continues to climb. Every additional dollar spent on the platform is less efficient than the last.

Marketers can use a simple rule of thumb to estimate the value of marginal cost in cases when the average cost keeps increasing with additional spend. When the marginal cost is increasing, it may be roughly one-half that of the average cost. So, for example, if the average customer acquisition cost through Facebook is $70, marketers can estimate that the true marginal cost is $140.

The hunt for alternatives

Where can brands turn once they’ve hit their saturation point? That’s been the question for several years now.

In their hunt for incremental growth, marketers often ignore one of the most established alternative channels: TV. Most growth marketers have aggressively tested into alternative digital channels like Snap, Pinterest, or TikTok, but TV remains the road less traveled, in part because of the higher barriers to entry, and in part because those marketers haven’t been able to measure it the same way as digital channels.

Among all marketing platforms, TV excels at offering scale. This can be best seen by comparing the marginal cost curves of TV and digital platforms in the graph below:

For brands looking to untether themselves from Facebook dependence, TV (yes traditional linear TV) remains a scalable and viable proposition. TV also provides a durable mechanism for getting more from the digital channels where growth marketers already have a significant presence. That is, provided those brands take the same discipline of measuring marginal CAC to the new medium.

For brands looking to untether themselves from Facebook dependence, TV (yes traditional linear TV) remains a scalable and viable proposition. TV also provides a durable mechanism for getting more from the digital channels where growth marketers already have a significant presence. That is, provided those brands take the same discipline of measuring marginal CAC to the new medium.

After all, TV has a saturation point, too.

Tatari is a data & analytics company focused on buying and measuring ads across linear and streaming TV.